BEYOND MR AGASSIZ ́S PHOTOGRAPHIC SALOON:

THE RAINFOREST AND THE ROLE OF INDIGENOUS AND MESTIZA WOMEN.

SANDRA BENITES E ANITA EKMAN, 2021.Beyond Mr. Agassiz’s Photographic Saloon, by Anita Ekman with Edu Simões, 2021. Digital collage using photo by Edu Simões (Floresta de Mangue, Série Amazônia, 2021) and detail from photo of an unnamed Brazilian woman by Walter Hunnewell, 1865, Peabody Museum, Harvard University, PM 2004.24.7640

Beyond Mr. Agassiz’s Photographic Saloon, by Anita Ekman with Edu Simões, 2021. Digital collage using photo by Edu Simões and detail from photo of an unnamed Afro-Brazilian woman by Walter Hunnewell, 1865, Peabody Museum, Harvard University.

Text produced from the dialogue between Sandra Benites (a Guarani Nhandeva PhD candidate in anthropology at the National Museum of Rio de Janeiro and curator of Brazilian art at the São Paulo Museum of Art - MASP) and Anita Ekman (a Brazilian visual and performance artist) about the article written by Christoph Irmscher (Chapter 7 - “Mr. Agassiz's 'Photographic Saloon.'” ) in the publication To Make Their Own Way in the World: The Enduring Legacy of the Zealy Daguerreotypes, edited by Ilisa Barbash, Molly Rogers and Deborah Willis. Co-published by Aperture and Peabody Museum Press, 2020.

In the opening of Chapter 13, “Exposing Latent Images: Daguerreotypes in the Museum and Beyond”, in the book “To Make Their Own Way in the World: The Enduring Legacy of the Zealy Daguerrotypes”, the author and editor Ilisa Barbash (curator of the Harvard Peabody Museum) quotes the artist Carrie Mae Weems:

“I knew I couldn't leave them where they were. I couldn't leave them when I found them. So, I should reconstruct and build a new context for them so that they could take on a new life, a new life, a new imagery, a new meaning, something that would question their historical paths and at the same time propel them forward to the future.”

- Carrie Mae Weems, on seeing the Zealy daguerreotypes for the first time.

Carrie Mae Weems’s response to the daguerreotypes, which was reaffirmed by Ilisa when she proposed this publication, makes it possible that 156 years after these images were taken, they can be discussed within Harvard University itself, by an Indigenous Guaraní Nhandeva woman, Sandra Benites. Sandra is a curator at MASP and a doctoral student in anthropology at the National Museum in Rio de Janeiro, and she has been in dialogue with Anita Ekman, a Brazilian visual and performance artist, in preparation for the video presentation “Race, Representation, and Agassiz's Brazilian Fantasy”, to be held on April 1, 2021.

Reaffirming the importance of the review of museum collections in the decolonial debate, we believe that we need to “plant” other perspectives and imaginaries in relation to the 1865-1866 Thayer Expedition. The two of us, as an Indigenous and a Mestiza woman, are particularly focused on the representation of the bodies of Indigenous and Mestiza women in the photographs produced by the leader of this expedition, the Swiss-American biologist and geologist Louis Agassiz. We hope that by doing so, we can open a discussion with Black and Afro-descendant women about these works. To initiate this process, we direct our attention beyond the limits of the yard that served as a “photo salon” for Agassiz in Manaus: the rainforest.

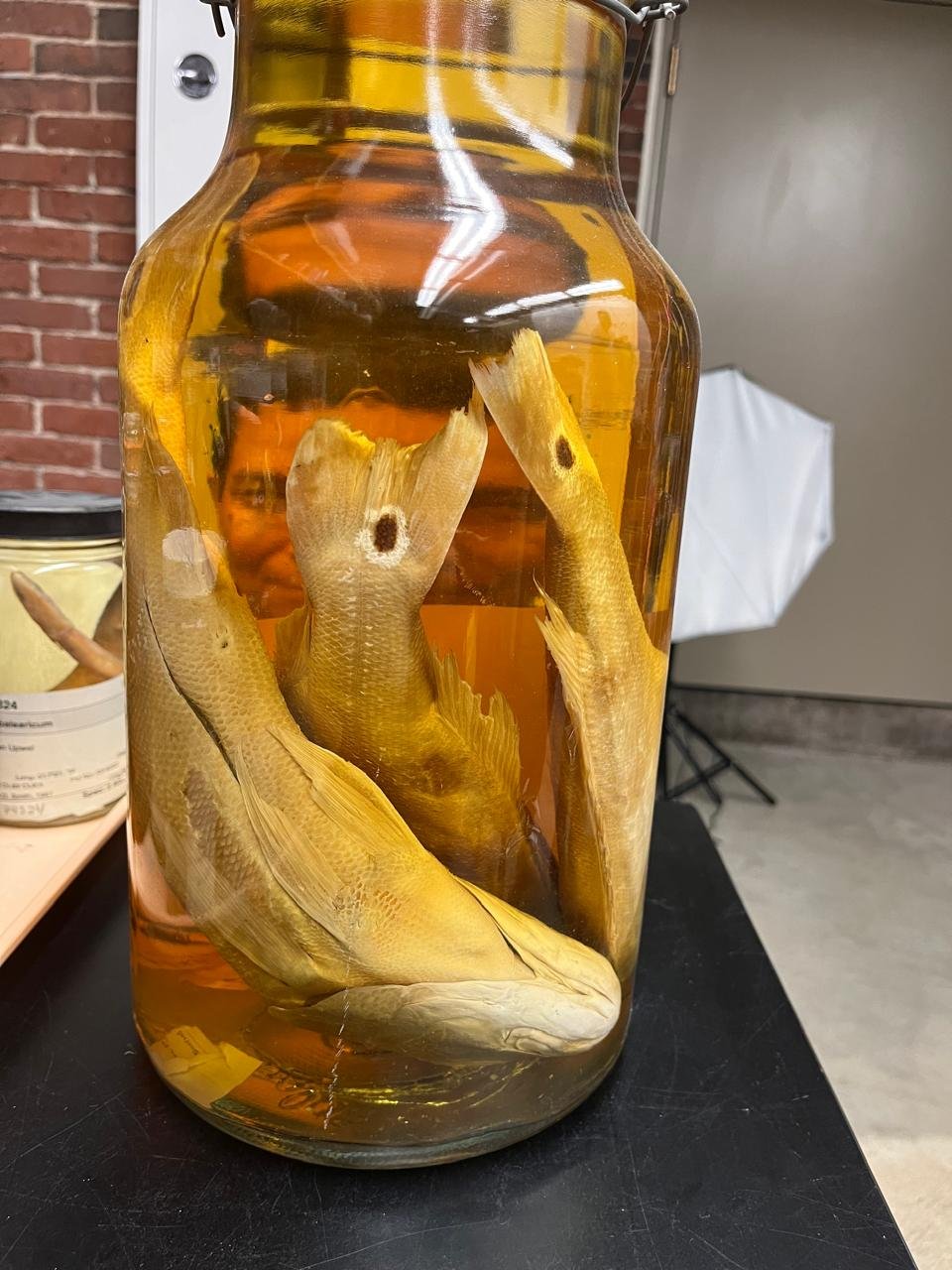

We take this approach for a number of reasons: for one, it was the rainforest itself that inspired the “anti-evolutionist” Thayer Expedition, which, besides Agassiz’s daguerreotypes, also endowed Harvard with the largest collection of Brazilian fish gathered in the 19th century.

The Brazilian Amazon also hosted the important studies carried out between 1848 and 1852 by a lesser-known contributor to the theory of evolution, Alfred Wallace. Both Agassiz and Wallace used the knowledge of Indigenous, Black and “Mestizo” men and women to carry out their work. It’s worth remembering here the fundamental role played by Agassiz’s Afro-Indigenous assistant Alexandrina in his expedition. In Agassiz’s racist formulation, “she had a mixture of Indian and black blood in her veins. She promises very well, and seems to have the intelligence of the Indian with the greater pliability of the negro... she is far quicker than I am in discerning the smallest plant in fruit or flower, and now that she knows what I am seeking, she is a very efficient aid."(1)

Agassiz exploited the bodies of women and men from the Brazilian Amazon in the construction of his photographic collection, while also appropriating their knowledge to create collections that remain at Harvard to the present day. The knowledge of those who were born and live within these forests is still not properly valued and recognized, yet it continues to be appropriated by scientists today, an undeniable legacy of the scientific racism which Agassiz espoused. In the words of Agassiz:

“A large number of the trees in these forests are still unknown to science today: however, the Indians, these practical botanists and zoologists, have a perfect understanding not only of their external forms, but also of their different properties. This empirical knowledge of the natural objects around them is so extensive that to gather and coordinate the scattered notions in the different locations of this region would ... greatly contribute to the progress of science; It would be useful... to write an encyclopedia of the forest dictated by the tribes that populate them. It would be... an excellent way to collect data, going from village to village, telling the Indians to harvest the plants they know, to dry them and to label them according to the local common names and inscribe, below these titles, alongside their botanical characters... indications regarding their medicinal or other properties."(2)

Lithography of Alexandrina. Digital Collage by Anita Ekman with Edu Simões Amazon Series, 2023.

"Fish people” by Anita Ekman with João Paulo Lima Barreto in the collection of fishes created by Agassiz (Thayer Expedition) - Museum of Comparative Zoology Harvard, 2024.

In his letter to D. Pedro II in which he suggests the creation of an encyclopedia of Indigenous forest knowledge, he concludes:

“For now, it is a knowledge that only the Indians have, and while there are still Indians it would be prudent to create a commission that, from their mouths, collects precise information that cannot be obtained from other sources.”

This relationship of how and why something is known, (especially if that “something” is the forest), is at the core of the discussion about the decolonization of museum collections and society as a whole.

A second reason for our proposal to analyse the forest is that, for those of born in the womb of a forest that has lost about 92% of its original vegetation cover (the Atlantic Rainforest or Ka’a guy Porã in Guarani), to be really capable of driving this “something” proposed by Carrie Mae Weems into the future - or to put it another way, so that the future itself can actually exist - we need forests to be at the center of the debate.

Brazil is the country with the greatest variety of plants in the world: 46,097 species, 43% of them endemic). This immense biodiversity is mainly due to the forests within Brazilian territory, the result intensive, precolonial Indigenous environmental management. Recent studies suggest that 60% of the Amazon rainforest is anthropogenic, that is to say, planted and cultivated by human hands before colonization (3).

When we refer to rainforests, we would like them to be understood as plural and specific. The global image of Brazil associates the idea of the rainforest and the Indigenous peoples that live within it exclusively with the Amazon. However, it is important to note that it was within another tropical forest, the Atlantic Rainforest, occupied by several indigenous cultures among them the Guarani (Sandra Benites’s ethnic group, see map), that one of the key stages in the history of the Atlantic World unfolded.

According to Sandra: “Decolonization requires that we think about two aspects of history. One is the narrative of the racist colonization process put in place by the white colonizing invaders, who have spread this viewpoint around the world, including in Brazil, excluding, disrespecting also erasing Indigenous peoples. Because it is an erasure, it is a denial, it is a silencing of Indigenous enforced by the idea of white colonization. If this idea didn’t exist, if we had the autonomy to discuss our own way of thinking, the way we see beings on Earth, I would say it like this because we are beings on Earth, I would say that this would be more democratic. If these thoughts crossed over, if the Arandu (wisdom) could be intermixed, the Indigenous Arandu with the scientists' Arandu, it would be a way of curing history itself.

And the other aspect is what we have been doing until today, and only recently have we been able to actually occupy some spaces, such as my position as a curator, being at MASP, as artists, as academic intellectuals, as leaders, all these Indigenous people are circulating amongst the whites, making bridge with them, taking this idea and this thinking in how we deal with the world, in fact explaining this to the Juruá (Non-Indigenous people) with the objective of generating partnerships and dialogue between the Juruá and Indigenous people, we can promote this dialogue. And this dialogue is a huge effort that we are making for the Juruá to understand our concern about earth beings, and this isn’t just a recent concern. Ever since the invasion, we have always had this concern, which is why we have always fought in various ways, whether as artists, leaders, academics, writers and in many ways, all Indigenous people have been fighting over these issues. That’s why I think it’s important that we explain this for the people at Harvard, trying to translate this wisdom of ours. Because most of the time there are no words or writing, there is only living, only experience will explain our thinking. That's why we Indigenous people have this question of practice, the question of orality, which leads us to continue to produce our knowledge so that we can take it forward to the next generations as a legacy, as knowledge, so that they also continue to learn to deal with the all the Earth’s beings.

Title: Tupi Valongo - Cemetery of New Blacks and Old Indians.

The skeleton of a Bantu woman in the largest African cemetery outside the African continent: The Cemetery of New Blacks. Located near the port of Valongo. Africans who arrived dead or died in the Valongo market were thrown by the thousands in the soil there. This was also the site of an ancient Tupi Indigenous village and a Sambaqui (a mountain of shells built by the first inhabitants of the Atlantic coast, often used to bury their dead). Our dead are inseparable in this land.

Cemetery of New Blacks. Instituto de Pesquisa e Memória Pretos Novos*, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. 2017. by Anita Ekman.

It was within the Atlantic Forest that one of the main themes in this publication, the slave trade, was consolidated. For this reason, it was in the belly of Ka'aguy Porã (in Guarani literally the beautiful and sacred forest) where many of the 12 million enslaved Africans brought to the Americas landed. The total number of Africans who were forcibly taken to the United States combined with the total number of enslaved Africans who landed in the Caribbean is still lower than the 4.8 million Africans who landed in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest. Most of them landed in the city of Rio de Janeiro, through the Valongo Wharf, the largest slave port on planet Earth, where about 2 million people transported from Africa arrived. To put this in perspective, Rio de Janeiro received more than four times the number of slaves than the entire United States.

This fact did not go unnoticed by Agassiz, who requested that portraits of “blacks of pure blood” be taken for him in the city of Rio de Janeiro by Messrs. Stal [sic] and Wahnschaffe, with the intention of integrating them into his collection of daguerreotypes of ‘inferior human types’ (Indigenous, Mestizo and Black) taken in 1865 in the city of Manaus in the Brazilian Amazon. As Christoph Irmscher noted in his article, for Agassiz such photographs implied that: "(...) conclusive proof It is interesting to note that for Agassiz’s rival Charles Darwin, the Atlantic Rainforest played a significant in the development of his revolutionary theory. Darwin, who had visited Brazil in 1832, recorded in his diary his astonishment at the diverse beauty of the forest as well as his indignation about slavery. Ildeu Moreira (who organized a publication gathering all of Darwin's writings on Brazil) highlights: "The impact of Darwin's passage through Brazil was far from minor, motivating him to ask 'where does diversity come from? (...) In several excerpts he says that one of the things that struck him most was the diversity of tropical nature that he saw in Salvador and Rio”.

Darwin also recorded his considerations about the horrors of the slavery in Rio: “Near Rio de Janeiro I lived opposite to an old lady, who kept screws to crush the fingers of her female slaves... I have seen at Rio de Janeiro a powerful negro afraid to ward off a blow directed, as he thought, at his face... And these deeds are done and palliated by men who profess to love their neighbours as themselves, who believe in God, and pray that His Will be done on earth! It makes one's blood boil, yet heart tremble, to think that we Englishmen and our American descendants, with their boastful cry of liberty, have been and are so guilty.”

It is important, however, to emphasize the criticism proposed by Janet Browne, professor of history of science at Harvard University, concerning Darwin’s views on race and gender. We highlight here: (...) for the naturalist "sexual selection among humans could also affect mental characteristics such as intelligence and maternal love", even within racial groups, and he wrote: "Man is more courageous, fierce and energetic than the woman, and has more inventive genius.”

The devastation of the Atlantic Rainforest produced commodities such as sugar and gold, extracted through the slave labor of Indigenous and African people, assisting in the accumulation of resources and the development of capitalism in England, while the nineteenth century slave trade was a source of wealth for traders from the United States.

Tupi Valongo - Commodities Fronteir (Sugar, Gold and Mate) by Anita Ekman with Julio Gárcia (Guarani Mbya) and Leonardo Castro. Performance at Engenho da Lagoinha in the city of Ubatuba in São Paulo. This mill is famous for being the first to produce white sugar in Brazil.

The Deepest South: that is what the US historian Gerald Horne called Brazil. Despite federal legislation prohibiting . American citizens and vessels to take part in the slave trade, ships built in the US would nevertheless leave the ports of New England for Brazil. That is where the slave trade was the most profitable - “a veritable El Dorado”, as Horne put it.

As W.E.B Du Bois observed, the slave trade to the Americas, during its busiest and most profitable age, came to be carried on “principally by United States capital, in United States ships, officered by United States citizens, and under the United States flag”. The U.S. was one of the countries that benefited most from Rio’s lucrative trade in human souls. The majority of transported people were sold at the Valongo wharf market, with US slave traders often overseeing the sales and reaping the profits.

“Transatlantic Colors” - Índigo and Gold by Anita Ekman with Modou Sall in September 2019, Valencia, Spain.

Although the Transatlantic slave trade is not the central theme of our analysis, what we would like to underline is that this trade is inextricably linked to the history of devastation in these forests and consequently the history of their Indigenous peoples. Yet the discussions that revolve around the “Atlantic World” still continue to study African slavery in isolation.

By leaving out Indigenous peoples and their various strategies of resistance and alliance with people of African descent within their forests from an analysis of the “Atlantic World”, we lose the possibility of advancing in research that is concerned, for example, with the real dimensions of Indigenous slavery in this territory.

We would then like to point out that it is impossible to deconstruct and rebuild other contexts to look at the photographs produced by Agassiz if we do not understand the history of the bodies of the peoples of the forest according to their own ontologies. We also need to approach the real history of what these bodies were actually subjected to, looking at the inseparable link between these bodies and the Earth's own body. This allows us to understand that:

(...) the indigenous populations of the colonial Amazon went through a century and a half under the pressure of enslavement. Padre Antônio Vieira estimated a number of two million Indigenous people killed in the process of enslavement until the middle of the sixteenth century (Vieira, 2013, p.226). (...) reliable sources suggest that somewhere between 110,000 and 390,000 Indigenous people were enslaved between 1680 and 1750 in the Amazon region (Dias, 2019). By way of compari- son, between 1693 and 1807, 91,454 Africans were brought to Amazonian ports as a result of the transatlantic trade (Martins, 2015, p. 93 and 105). in MARTINS, Diego de Cambraia. ‘Some Notes: Indigenous Slavery in the Colonial Amazon and Manaus in the 19th Century’. Working Paper, 2021.

In the southern Atlantic Rainforest, one of our collaborators, historian Freg J Stokes, systematizing the data from primary sources, concluded that from 1520 to 1680 somewhere between 152,000 and 227,000 Indigenous people, over 100,000 of them Guaraní speakers, were captured by Portuguese slave raiders (Stokes, forthcoming).

Freg J. Stokes, 2021.

Returning to the Carrie Mae Weems’s reaction when she saw the Zealy daguerreotypes for the first time, we would also like to record our impressions here in the first conversation we had about the photographs presented in the article “Mr. Agassiz`s Photographic Salon”, written by Christoph Irmscher.

Anita, at Sandra's request, summarized for her the historical context in which Agassiz produced such photographs, explaining Darwin’s theory of evolution and the importance that this theory still has in the way the Juruá (Non-Indige- nous people, literally ‘hairy mouths’, in reference to the beards of the colonizers) view and understand nature. Sandra then asked:

Sandra: “Anita, I've heard something about this Juruá idea of the evolution of species before, that humans evolved from monkeys. But have the people in Harvard heard the story that the Vulture was a person? So, I would like to make a provocation that has to do with racism that is still very present not only against the appearance of our bodies as in the photographs by Agassiz, but also in relation to our way of thinking and existing... will Non-Indigenous people really be willing to consider the discussion about "to be or not to be" from our point of view? Because we have to go further, not only to discuss Agassiz’s or Darwin’s theory, but to consider the fact that we Indigenous people also need to be heard and respected in the way we think about the fundamental questions concerning human beings and nature.

While historians seek to understand the history of the indigenous people based on their investigations from the colonial period, for example, we started from another time reference, from which we make our own pathway through history. We call this the time of origin, "Ore ypyrã". Non-Indigenous people call this mythology, but for us this separation between history and myth that Non-Indigenous people make, it does not exist. In Guaraní origin narratives, there is the past, the present and the future and there is a teaching about how we should live on this Earth, about why the Earth is a sacred body: it is the living body of a woman, she is the body of our first mother, Nhandecy Eté. When we step on the earth we step on a woman's body. So we must step lightly, without leaving marks.

In the beginning times, there was a man, who, similar to the men of today, did not respect the bodies of animals. He kicked dead bodies, he did not care about respecting anything beyond his own whims. In other words, he was only concerned with himself and did not believe that nature has rules that need to be respected. So this man was transformed into a vulture, a bird that only eats only rotten meat from other animals, to help clean the body of our mother, Nhande- cy Eté, the Earth. In our thinking, from the beginning, there exists the idea that we are here on Earth within a delicate balance, and at the same time a beautiful, quite feminine balance. And that this needs to be respected because it is profoundly sacred. Nhandecy Eté, our first mother who is at the same time the Earth, she is the basis of all Guarani thinking concerning how we, beings of the Earth (both human and non-human) should relate to this mother's body.

The Earth, the body of Nhandecy Eté has been violated since colonization, just like the bodies of Indigenous women. The way of perceiving and acting and speaking, of being a woman, is being as equally disrespected and massacred as the Earth's own body. I always say this: it’s difficult to admit, but Brazil is the child of rape, of Indigenous women and then Black women, this is the question that is often hidden. The Brazilian, he who feels like a real Brazilian, in reality he is the son of a rape. The miscegenation that Agassiz denounced, in other words, is charged with this silencing that women still go through today, that violence that is felt against our bodies inside and outside the villages until now.”

“Tupi Valongo - Kunhanguereko. The Woman's blood”. Sandra Benites and Sandra Nanayna by Anita Ekman, 2021.

“We speak a lot these days about traditional Indigenous knowledge: that it should be valued, assimilated, incorporated into our stock of knowledge and, as far as possible, returned, that is, reciprocated.

(...) In fact, our conception of traditional knowledge does not imagine that the incorporation of this knowledge will change our image of knowledge itself. We are only after the contents of these knowledge traditions, but their form, in truth, is not the packaging we prefer. It is imagined possible to separate these contents from the ways in which they are articulated in Indigenous thought.

However, what distinguishes traditional Indigenous knowledge from our Western knowledge, whether traditional or non-scientific - is precisely the form far more than the content. (...)

(...) If we could characterize in a few words a basic attitude of all Indigenous cultures on the continent, I would say that the relations between a society and the components of its surrounding environment are conceived of and lived as social relations, that is, as relationships between people.

(...) Nature is not natural, that is, passive, objective, neutral and mute, as it is for us; humans do not have a monopoly on the position of agent and subject. We are not the only ones to understand something that is essentially ignorant of itself - which is how we conceive nature - while we have this gift or this curse - depending on how we consider it - on the contrary, knowing that we know something while animals, plants, stones don't know anything, and what they know they don't know they know - the poor apes, the superior primates, who know something, as we admit, but don't know what they know how we know it and so, therefore, we are naturally special. This is the point: in Indigenous knowledge about nature, humans are not the only focus of the active voice of cosmological discourse.

If I were to continue with this contrast, I would say that the category that dominates the relationship between man and nature in our modern tradition is the category of production”.

Eduardo Viveiros de Castro in Visões do Rio Negro. ISA.

Title: To Make Their Own Way in the World. Performance by Anita Ekman in the Atlantic Rainforest, Ubatuba, Brazil. 2021. Photo: Pedro Ekman.

Anita: Anheté, it's true Sandra. To discuss racism, it must be admitted that it functions as a type of fast, violent and murderous machine, through this way of perceiving nature in the capitalist mode of production. I have a friend, the historian Tâmis Parron*, he says that we should start calling capitalism by its real name, which is “racial capitalism”.

We must discuss what is behind the names we give to things. For example, what you highlighted before about what it means to be Brazilian. There is a very famous phrase from the “Anthropophagic Manifesto”, playing on Hamlet’s soliloquay, it goes,: “Tupi, or not Tupi that is the question”. (The Anthropophagic Manifesto, written by Oswald de Andrade (1890 - 1954), was published in May 1928, in the first issue of the recently founded Revista de Antropofagia, a vehicle for the diffusion of the Brazilian anthropophagic movement).

But the literal question never discussed in "Tupi or not Tupi" is really the story of these Indigenous women, raped, silenced and forgotten. In this sense, while the anthropophagic movement preached that the devourer could assume the point of view of the devoured and the devoured of the devourer (the basis of perspectivism as suggested by Viveiros de Castro) as one of the key elements to think about the Brazilian nhandereko (in Guarani: the way of being and living), if we replace the verb "devour” with "rape" in the constitution of that "being", then the transmutation of perspectives is no longer possible. It is as if the point of view of women could never occupy a central place, as if it were not possible to think of brazil through the history of its women, as if the viewpoints of women should always be covered up like their bodies, because women cannot be the protagonists of any story. What happened to Tupi and Guaraní women is no different from the experience of Macro-Gê, Karib, Pano, Tukano, or other Indigenous women, or the experience of Black women, this is a colonial violence that has been perpetuated in our society and just like racism, it continues to claim victims. Brazil has one of the highest rates of femicide in the world, ranking fifth in the world in the violent deaths of women. This theme of femicide, which is also a central theme in your doctoral thesis Sandra, I think it shows how urgent it is to debate these topics. It's like how you put it Sandra: “There is no future without the past! There is no better future without touching the bad wound of the past.”

So, my question here is that if from Agassiz’s fantasy of “Brazilian miscegenation” we redirect our gaze to the history of Indigenous women, this changes what we as Brazilian women, daughters of this rape, can build as another consciousness, specific to what we are as Brazilians, but also located at the crossroads of globalization.

“The consciousness of the Mestiza”. Series Ocre Cerâmica Polícroma da Amazônia by Anita Ekman, MUSA - Museu da Amazônia, Manaus, 2022. Picture by Luca Meola.

La mestiza constantly has to shift out of habitual formations (...) toward a more whole perspective, one that includes rather than excludes. (...) The new mestiza copes by developing a tolerance for contradictions, a tolerance for ambiguity. (...)

She has a plural personality, she operates in a pluralistic mode—nothing is thrust out, the good the bad and the ugly, nothing rejected, nothing abandoned. (...) That focal point or fulcrum, that juncture where the mestiza stands, is where phenomena tend to collide. It is where the possibility of uniting all that is separate occurs. This assem- bly is not one where severed or separated pieces merely come together. Nor is it a balancing of opposing powers. In attempting to work out a synthesis, the self has added a third element which is greater than the sum of its severed parts. That third element is a new consciousness—a mestiza consciousness—and though ft is a source of intense pain, its energy comes from continual creative motion that keeps breaking down the unitary aspect of each new paradigm.

En unas pocas centurias, the future will belong to the mestiza. Because the future depends on the breaking down of paradigms, it depends on the straddling of two or more cultures. By creating a new mythos — that is, a change in the way we perceive reality, the way we see ourselves, and the ways we behave — La mestiza creates a new consciousness.

(...) The answer to the problem between the white race andthe colored, between males and females, lies in healing the split our languages, our thoughts. A massive uprooting of dualistic thinking in the individual and collective consciousness is the beginning of a long struggle, but one that could, in our best hopes, bring us to the end of rape, of violence, of war.

Gloria Anzaldúa. The consciousness of the Mestiza / Towards a new consciousness.

Anita Ekman and Sandra Nanayna Tariano, Performance Ritual, “Ocre –Pele e Pedra” (“Ochre—Skin and Rock”), Toca Pinga do Boi, Parque Nacional da Serra da Capivara, Piauí, Brasil. 2019.

In a way, this is one of the main discussions within a previous performance which we created together, 'Tupi Valongo - Cemetery of New Blacks and Old Indians' with Hugo Germano, Sandra Nanayna, Dani Ornellas, Nzo Oula and

Marcelo Noronha. The opening sentence of this performance is relevant to this discussion about Agassiz's photographs:

"When the Europeans arrived here, they thought that we Indigenous women were naked, but we were not, we were dressed in paintings."

So, the discussion about the dressed body vs. naked body in Agassiz’s photograph, is charged with an even more devastating meaning that Non-Indigenous people can easily miss: the obligation to wear European clothing versus the prohibition of body painting or "tattoos". In the book she wrote with her husband, A Jorney in Brazil (1868), Elizabeth Agassiz covered this theme when describing a Mundurucu Indigenous couple:

“It might be thought that the fantastic ornaments of these Indians would effectually disguise all pretence to beauty; but it is not so with this pair. Their features are fine, the build of the face solid and square, but not clumsy, and there is a passive dignity in their bearing which makes itself felt, spite of their tattooing. I have never seen anything like the calm in the man’s face; it is not the stolidity of dulness, for his expression is sagacious and observant, but a look of such abiding tranquillity that you cannot imagine that it ever has been or ever will be different. The woman’s face is more mobile; occasionally a smile lights it up, and her expression is sweet and gentle. Even her painted spectacles do not destroy the soft, drooping look in the eyes, very common among the Indian women here, and, as it would seem, characteristic of the women in the South American tribes; for Humboldt speaks of it in those of the Spanish provinces to the north.

(...) Major Coutinho tells us that the tattooing has nothing to do with individual taste, but that the pattern is appointed for both sexes, and is invariable throughout the tribe. It is connected with their caste, the limits of which are very precise, and with their religion. The tradition runs thus, childish and inconsequent, like all such primitive fables."

Body painting, like ceramics and rock art, is deeply connected to the domain of women, where the bond to the body-earth is present. Body painting is actually a way of informing, connecting and transcending with our own body these other dimensions of Ore ypyrã (The Time of Origin) but it also literally transports us to the very origin of humanity.

Anita Ekman and Sandra Nanayna Tariano, Performance Ritual, “Ocre –Pele e Pedra” (“Ochre—Skin and Rock”), Toca do Salitre (São Raimundo Nonato, Piauí, Brasil). 2019.

I think this question of looking at the body and seeing the body of the earth through it (and vice versa) is a key issue for Non-Indigenous people that needs to be addressed. In a way, what is painted on the body or on the earth-body (literally the ceramic body whose material is the earth itself, just as in rock painting) has a deep and ritual bond. The idea of the existence of this body-earth relationship through painting, is present among Indigenous peoples, but it is not limited to them alone. This relationship has, in several ways, been revisited since the dawn of humanity around the world on other continents, being a profound mark – made in ochre - of a performative knowledge of ourselves as beings of the earth. I believe that this connection has been present in the memory of human imagination for the last 70,000 years - and it is of great importance to look at these human ocher marks left on the body of the earth as a valid alternative to rethink our presence on the planet.

In this sense, I think about what Sandra Nanayna, an indigenous (Tukano-Tarian) from Rio Negro, Amazonas, said when we created the performances of the Ochre project ( https://theodreview.com/2020/11/30/on-anita-ekmans-ochre/ ) together in the Serra da Capivara National Park: "being like the stone people is the great dream". We can remain present on the Earth in a relationship with the sacred and beautiful body of the Earth, as happens in rock art - this is at least be one way to re-imagine how we leave our marks on the sacred body of Nhandecy eté.

I would like to emphasize the importance, then, of understanding the role of women in the arts, in the creation of these imaginaries. In this sense, the Thayer Expedition remains to discussion in other fields of art and not only in relation to the history of photography. The Thayer Expedition also brought the disciple of Agassiz, the Canadian-American geologist Charles F. Hartt, to Brazil. Hartt, who later converted to Darwinism, was a pioneer in Amazonian archeological studies. He was the first outsider to reproduce the rock art of Monte Alegre (a site visited 20 years earlier by Wallace and where the oldest vestiges of human presence in the Amazon are found, dating back 11,200 years). Hartt was also the first to write about and publicize the Marajoara ceramics to the world.

Anita Ekman: Tupi or not Tupi. How to (re)write the history of Brazil. 2022. Ocre Marajó Series - Emílio Goeldi Museum of Pará.

The series is part of the curatorial research for the project Ore ypy rã - Tempo de Origem, by Sandra Benites and Anita Ekman. Made possible with the Visual Arts Scholarship -2021 granted by the Goethe Institute and the French Consulate in Rio de Janeiro.

by Cristiana Barreto and Freg J. Stokes, 2022.

Intrigued by this richly adorned pottery, Hartt drew attention to the importance of the role of women artists in the origins of the South American continent. Charles Hartt intended to, through studies of ornaments, link his work with Darwin's evolutionary theories. His racist thinking revealed itself when he considered that only "civilized women" had the capacity to represent nature, with their decorative arts naturally being more "evolved" and beautiful.

So with both the Agassiz and Marajoara collections that began their life through the Thayer expedition, I think that one of the main messages that remains latent in this discussion is how in fact we are going to decolonize museum collections and amplify these other visions. I also believe that these visions need to be articulated in a way where Indigenous, Black and Mestiza women can have the necessary space to deepen their dialogues in relation to their stories, where in fact we can find another starting point to rethink ourselves in Yvyrupa (The land that is one and has no borders, in this sense the American continent). I believe, therefore, that it is through Brazilian contemporary art and especially through what Indigenous artists, thinkers and curators bring (See attached work Tudo é Gente, by Denilson Baniwa) that we can rethink our role within these forests, directing ourselves to the “Tenonde porã”, a horizon that is only good and beautiful if we all arrive there together.

So, by confronting the horror of these photographs, we can look at the history of the women who came before us and who are in us, in body or beyond that, in spirit, and we can envisage this other future. In this sense, I believe that Guara- ni thinking about Nhee, which is at the same time designates the word and the spirit, shows what we want to express, which is in reality what you locate as a fundamental concept Sandra, the importance of Nhemonguetá for women, the exchange of words and therefore a conversation between spirits, the recounting of the stories we tell about ourselves as women. It is in this strengthening of dialogue between women that we open the way to find strength, to strengthen ourselves together and overcome so many injustices committed against our bodies and the body of the very land we inhabit.

Sandra Benites: This idea of the earth body and we who are earth beings (human and non-human) is the fundamental theme. Because we need to get along with non-human beings. Non-humans understand people. But Non-Indigenous people do not understand that they understand this, nor that we Indigenous people know that we must understand this communication between the beings of the Earth.

I think that all this makes us think deeply about the true nature of freedom. That is what freedom is for me, it is being able to recognize within this immense diversity of ways of being and thinking, that there is space and the possibility of meetings, where exchange exists to strengthen us as beings on Earth. What I hope then is that, based on what is good and beautiful in the encounter of these different ways of being and existing, of these voices, we can find a way to walk together towards a common horizon where the body of the Earth will be as cared for, as will the body of us women, and as will the life of all beings on Earth, human and non-human. We hope that we can, by continuing to tell ourselves stories from the beginning times, postpone the end.

"Our time specializes in creating absences: in the meaning of living in a society, in the very meaning of the experience of life. This generates a great intolerance towards those who are still able to experience the pleasure of being alive, of dancing, of singing. There are small constellations of people scattered around the world who dance, who sing, who make it rain. The kind of zombie humanity that we are being summoned to integrate with does not tolerate such pleasure, such enjoyment of life. So, they preach the end of the world as a possibility to make us give up our own dreams. And my provocation about postponing the end of the world is exactly this, to always be able to tell one more story. If we can do that, we will be postponing the end." Ailton Krenak, Ideas to Postpone the End of the World.

Urn of Life. Series: Ocre Marajó -Ethnologische Museum Berlin. Ocre Marajo ritual performance by Anita Ekman with Marajoara urn (Pacoval style) in the collection of the Ethnologische Museum Berlin Germany. 2021. Photo by Nina Cavalcanti. The series is part of the curatorial research for the project Ore ypy rã - Tempo de Origem, by Sandra Benites and Anita Ekman. Made possible with the Visual Arts Scholarship -2021 granted by the Goethe-Institut and the French Consulate in Rio de Janeiro.